Your Anger Is Not the Problem

- Kimberly Best

- Jul 17, 2025

- 8 min read

Whether we're in the conflict or managing the conflict, anger is arguably the most misunderstood emotion in conflict situations. Rather than viewing it as something to avoid or suppress, we can learn to see anger as valuable information—a signal that something important needs attention and a potential catalyst for positive change. As a mediator and conflict management professional, I've witnessed how understanding and working with anger, rather than against it, can transform both individuals and relationships.

The Complex Nature of Anger

Anger is inherently tricky. On one hand, it serves an important function—alerting us to danger, real threats, injustices, and situations that require our attention. It energizes us to take action when we've been wronged or when our boundaries have been crossed. In healthy doses, anger can motivate positive change and protect our fundamental rights.

However, many of us have been raised with a very low tolerance for anger and often taught that anger itself is "bad" or inappropriate. Think about the response your caregivers had to you when you were angry. This cultural conditioning creates a paradox: we need anger as a normal and vital human emotion, yet we're often uncomfortable when it appears—both in ourselves and others. I was one of those people who was raised that anger was bad—thus I was bad for being angry—and I still tend to feel guilty for being angry. Another paradox is how angry the people often are who are telling us to not be angry!

It's important to remember that emotions are natural reactions to perceived threat. No one thinks well or reacts well when feeling under attack—and it doesn't matter if you're meaning to attack.

The key isn't to avoid being angry, but to understand what anger is telling us and learn how to work with it constructively. When we deny or suppress anger, we lose access to important information about our—or the other person's—needs, boundaries, and values. When we let anger control our actions without reflection, we risk causing harm to ourselves and others.

Like unresolved conflict, unresolved anger doesn't just disappear—it festers and grows. Anger becomes problematic when it moves beyond its initial signaling function without our tending to it. Held anger can stress our bodies over time, narrow our attention so we lose sight of the bigger picture, cloud our judgment, and potentially drive us toward impulsive responses. Most concerning of all, unexamined anger often creates and escalates conflicts, often causing more damage than the original issue warranted.

But there's another trap that anger sets for us—one that can be even more dangerous because it feels so justified.

The Seductive Power of Anger

One of anger's most dangerous qualities is how seductive it can be. When we feel wronged, mistreated, or provoked, anger provides us with ready-made justifications: "Of course I'm mad—you made me mad. It's your fault." This emotional state can be falsely justifying, making us feel perfectly entitled to lash out or seek revenge.

Anger draws us into adversarial thinking, creating mental frameworks of right/wrong, victim/offender, prosecution and blame. It fools us into believing we're taking righteous action when we may actually be causing harm. When this happens, we often find ourselves looking back at angry episodes with dismay and regret, wondering how we let our emotions take control. And the conflict spirals out of control.

When someone becomes triggered or angry, our natural tendency is often to point out their emotional state or walk away from the conversation entirely. We might say things like "You're being too emotional" or "I can't talk to you when you're like this." "There you go again, getting angry!" While these responses may feel justified in the moment, they often shut down communication precisely when understanding is most needed.

When we make someone's anger the problem—rather than a signal about an underlying problem—we inadvertently shift into a position of moral superiority. I know this tendency well because it's been my own pattern. We focus on their "inappropriate" emotional response instead of trying to understand what's driving it. This approach transforms us from collaborative problem-solvers into judges of acceptable behavior.

I have learned that the moral high ground is not a good place to be—it keeps us stuck in an "I'm right, you're wrong," "I'm good, you're bad" mindset. When we hold back on self-righteousness and approach anger with curiosity instead of judgment, we create space for genuine understanding and resolution. Like most things, when we understand the complexity of something, we are less likely to judge it.

A Word on Triggers

Here's what's important to understand about triggers: first, we all have them and second, they happen before conscious thought—which means controlling them takes a lot of practice. When someone is triggered, their nervous system is responding to perceived threat faster than their rational mind can process the situation. This biological reality means that pointing out someone's anger in the moment rarely helps them regulate—it often escalates the situation further. It also means that it's not the time for negotiation. It's time to calm down. It's often the time when people quit the conversation. Anger has become too big and threatening.

The reality is that the more angry someone feels, the more important something likely is to them. This intensity warrants curiosity, not dismissal. When we can move past the initial trigger moment and revisit the conversation when everyone is calmer, we often discover legitimate concerns that deserve attention.

Remember, you're a biological being and so is the person you're at conflict with. Allow emotion—it's natural and necessary. We all have a breaking point and despite the expectations we heap on each other, we are all human. We need a baseline of understanding and trust before we can work together to find a way forward.

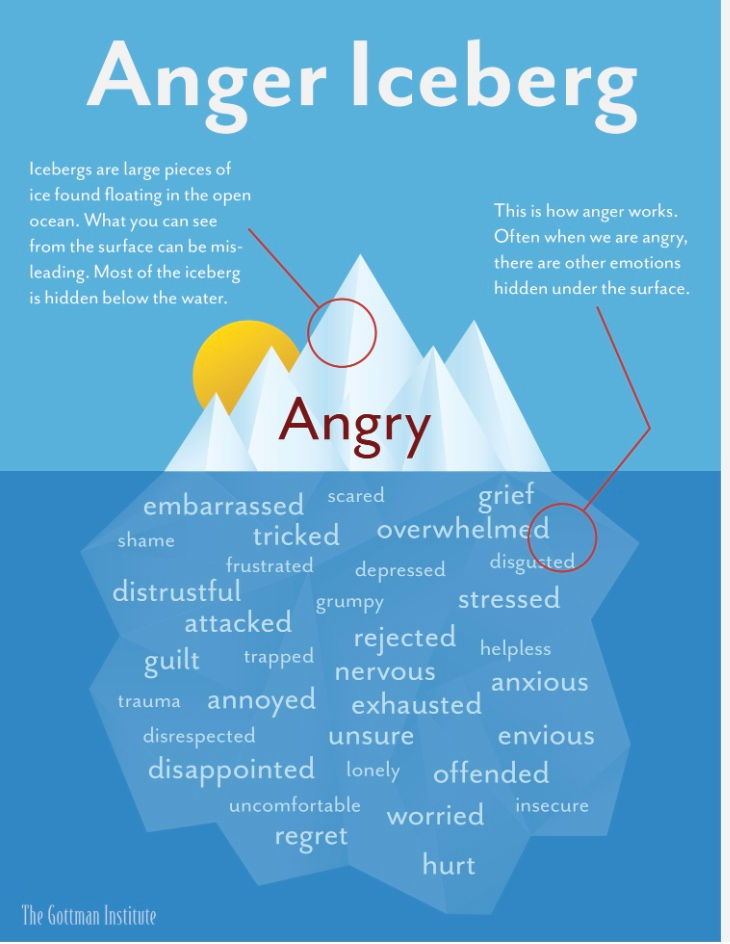

Looking Beneath the Surface: The Anger Iceberg

One of the most transformative tools I share with clients is the concept of the anger iceberg, developed by relationship researcher John Gottman. Most of us struggle to relate to people who are angry—their anger often triggers our own defensive responses, creating a cycle of escalation rather than understanding.

However, "anger" is a word that's a broad brushstroke over a lot of other emotions. Like an iceberg, anger is what we see on the surface but underneath lies a complex landscape of more vulnerable emotions: hurt, disappointment, loneliness, sadness, fear, feeling disrespected, left out, or unheard and many more. These underlying emotions are much easier to relate to and connect with than raw anger.

When someone expresses anger, instead of responding to the anger itself, we can look deeper and ask: "What might be underneath this anger? What need isn't being met?" Perhaps they're feeling unappreciated for their contributions, anxious about a change, or hurt by something that happened. These are emotions we can all understand and empathize with.

This same principle applies to our own anger. When we feel anger rising, we can pause and ask ourselves: "What am I really feeling beneath this anger? What do I need right now?" Often, we discover that we're seeking recognition, safety, connection, or respect—needs that are completely legitimate and can be addressed constructively.

Anger as Fuel for Positive Change

William Ury offers a powerful metaphor that captures the transformative potential of anger: anger is like gasoline—if you spray it around and somebody lights a match, you've got an inferno. But if we can put our anger inside an engine, it can drive us forward.

This metaphor perfectly illustrates the choice we have when anger arises. We can let it spray destructively in all directions, creating fires that burn relationships and escalate conflicts. Or we can harness that same energy constructively, using it to fuel positive action and meaningful change.

The difference is not in the presence or absence of anger, but in how we channel it. When we understand what our anger is telling us about our values, needs, and boundaries, we can transform that emotional energy into purposeful action that addresses root causes rather than just symptoms.

A Different Path Forward

Instead of treating anger as a wall that blocks communication, we can learn to see it as a door that opens into deeper understanding. The conversation might sound like: "I can see this is really important to you, and I want to understand what's driving your strong reaction. Can we take a moment to slow down and explore what's happening here?"

We are positioned to help by leaning in with empathy and truly listening—not for judgment or to find a solution, but to understand. Sometimes people just want to be heard. This requires us to engage in discussions, not debates, and to start with ourselves first.

Anger often creates a stopping point in our relationships and conflicts—a wall that seems to block any path forward. But when we understand anger and take away the stigma, we can transform that wall into a door, opening up opportunities for problem-solving and deeper understanding for everyone involved.

Practical Strategies for Managing Anger in Conflict

Here are key principles that can transform how we approach anger in conflict situations:

Focus on how YOU handle it, not what they do. It's not about them or what they do, but about how you respond. Listen to understand and encourage others to listen to understand as well. Move away from right/wrong, win/lose thinking.

Assume positive intentions. While our brains are wired to scan for danger, we can teach ourselves to default to assuming people mean well when they express anger or frustration.

It doesn't matter what you meant—what matters is what they received. We have a responsibility to communicate so people understand us, and to genuinely try to understand what they're communicating to us. Be open to their explanations and allow space for people to refine their thoughts and ideas as they work through what they're trying to express. We rarely get it right the first time.

Separate people from problems. Remember that the person expressing anger isn't the problem—they're likely responding to a real issue that deserves attention. Keep the focus on understanding and addressing what's driving the conflict rather than making someone's emotional response the central issue.

Listen for what's under the iceberg. When emotions run high, slow things down by listening for the deeper needs and concerns beneath the surface reaction. Use reframing and summarizing to show you're truly hearing them: "Let me see if I understand... it sounds like you're feeling..." This validates their experience while helping everyone gain clarity about what's really at stake.

Remember—it's ALL about relationships. When anger arises, it's easy to get so focused on being right or winning the argument that we forget what truly matters—the relationship with the person we're in conflict with. Care enough about the person that you don't have to make them wrong or make them lose.

Create space for collaborative solutions. Resist the urge to fix everything yourself. The people involved in the conflict often have the best insights into what might actually work. Solutions that emerge from collaboration tend to be more sustainable and effective.

Moving Beyond the Flames

True strength doesn't come from the intensity of our anger. It comes from our ability to respond to difficult situations with wisdom, courage, and compassion. When we learn to harness our emotions rather than being hijacked by them, we create space for genuine resolution and positive change. These are learned skills though. They don’t come to us naturally.

In conflict situations, this means choosing presence over reactivity, understanding over judgment, and collaborative problem-solving over winning. It means recognizing that while we cannot always control what happens to us, we can control how we respond—and that choice makes all the difference in transforming conflict into opportunity for growth and connection.

The next time you feel anger rising in a conflict situation, note it without judgment. Ask yourself what is causing the anger. Identify the need you have. Then take a breath and remember: you're standing at a crossroads. You can let this anger build walls that separate you from others, or you can use it as the key to unlock doors you didn't even know existed—doors to understanding, to resolution, and to relationships that are stronger because they've weathered the storm together.

Link to John Gottman’s Anger Iceberg:

Comments